Content warning: This article includes mentions of child abuse, sexual assault, homophobic, transphobic, and racist rhetoric and violence. If any of these issues have the potential to cause distress, please proceed with caution or contact the author for a summary.

—

The fear of the “other” has always played an important role in the human psyche and has had a significant influence on everything from mythology to politics. In Lovecraftian fiction, the other is presented in the form of beings from distant parts of the universe as well as unknown places on Earth itself: the star-spawn of Cthulhu, the Elder Things, the Deep Ones, et cetera. In Tolkien’s fantasy novels, the noble peoples of Middle Earth defend themselves against grotesque orcs and evil men from Harad and Rhûn. Modern horror films fixate on zombies, vampires, shapeshifters, and various similar creatures who imitate human beings yet are harbingers of death. And reactionary propaganda consistently portrays its choice targets as frightening others who must be defeated, lest they bring destruction in their wake.

The other is the most consistent feature of reactionary propaganda, even though its precise form tends to change depending on the historical epoch. People of different races or nations, people who practice different religions or lifestyles, and people who adhere to even slightly different iterations of the same culture have become the loathsome other at various points in time. In the modern world, one diverse group in particular has become such a target: gender and sexual minorities. With their increasing visibility over the latter half of the 20th century and the first two decades of the 21st, they are facing a new wave of reactionary fervor, the nature and potential outcomes of which are all too familiar to students of history.

Homosexuals, gender-nonconforming people, and others who fall under the LGBT+ umbrella are known to have existed throughout the past, as same-sex relations and third genders have been tolerated and even celebrated in different cultures across the globe. In many of these instances, what western conservatives would today consider abnormal forms of behavior or expression were thought to be natural and even integral parts of the given culture. In the ancient Greek understanding of sexuality, for instance, engaging in homosexual relations was a regular part of manhood, and to this day the Bugis people of Indonesia recognize five distinct gender roles which each have a respected place in society.

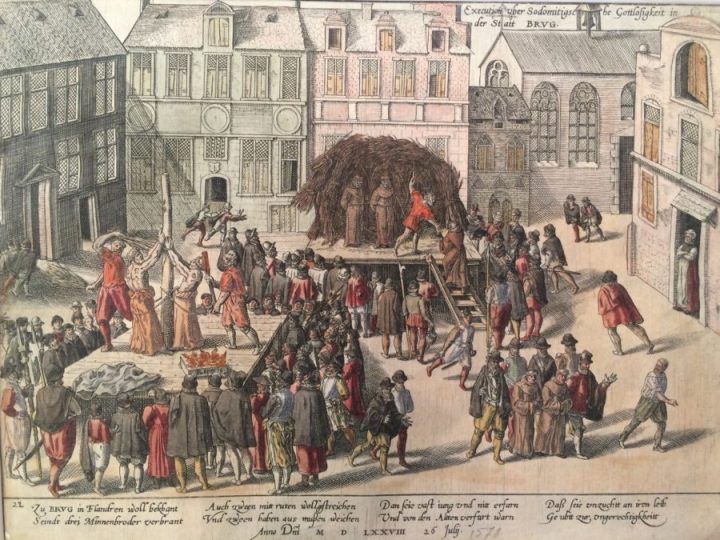

Much of this tolerance changed over time as the strict morals of the Christian and Islamic worlds were exported around the globe. By the 19th century, laws against homosexual behavior were on the books almost everywhere and a rigid dichotomy between male and female gender roles was imposed. As heterosexual and cisgender lifestyles became the strictly enforced norm, anyone who dared not to comply became a dangerous other who existed as a threat to the symbolic order, and defiant behavior would result in ostracization at best or torture and execution at worst. Thus the range of socially acceptable behaviors and expressions became narrow at the same time as racial and nationalistic ideologies arose to heighten people’s fear of everything foreign and unfamiliar.

Though the particular opposition to the other that became so common throughout the world in the early modern era was largely based on Abrahamic law and European prejudices, its roots go much deeper, penetrating into human psychology. In Phenomenology of Spirit, Georg Friedrich Hegel asserts that “self-consciousness only achieves its satisfaction in another self-consciousness,” or in different terms, one’s sense of self is only truly established in contrast to an other. Bernardo Ferro explains it this way: “self-consciousness recognizes itself successively as the negative of all otherness, as the desire to suppress that same otherness.” One person needs to know what they are not in order to know who or what they are, thus the self can not exist without the other.

This seems to be a natural ontological condition for human beings; I know I am me because I am not any of the people or things around me–they are all something other than me. But when applied to categories or groups of people, this self-other dichotomy begins to have effects more complicated than simple individuation, and often more dangerous. We can find a good summary of what tends to happen in Simone de Beauvoir’s introduction to her book The Second Sex:

No group ever defines itself as One without immediately setting up the Other opposite itself. It only takes three travelers brought together by chance in the same train compartment for the rest of the travellers to become vaguely hostile ‘others’. Village people view anyone not belonging to the village as suspicious ‘others’. For the native of a country, inhabitants of other countries are viewed as ‘foreigners’; Jews are the ‘others’ for anti-Semites, blacks for racist Americans, indigenous people for colonists, proletarians for the propertied classes.

The “vague hostility” mentioned by Beauvoir certainly exists for the individual in contrast to their surroundings; horror films, after all, frequently play at fears of ego loss or integration with some alien body, such as in John Carpenter’s The Thing. But this hostility becomes more pronounced when one’s sense of self relies on a group identity, when I am not merely me, whatever that might entail, but an extension of a fixed category which I must defend against redefinition or encroachment.

The purpose of Beauvoir’s book is to elaborate on the tensions between men and women, specifically the “othering” of women by men in western society. She explains that women’s position is such that they serve as the contrasting other for men, but due to the oppressive nature of patriarchal structures, they can not quite use men as their own other in order to define themselves. She explains that “reciprocity has not been recognized between the sexes… one of the contrasting terms is set up as the sole essential, denying any relativity in regard to its correlative and defining the latter as pure otherness.” This is because the way the masculine category has been traditionally upheld requires men to exercise power over the feminine category; for so many men, to be a man means to be oppressive in some way, hence the inability of women to exercise full control over themselves and their identity.

While this relation between men and women has often been masked with rhetoric of paternal care and wisdom, and while it does not always produce overt hostility, it does engender tensions that have great potential to erupt in angry or violent behavior. For the man particularly invested in manhood it is often necessary to be hostile towards anything that might be defined as feminine when it is displayed outside of the realm to which it is consigned; this includes women entering male spaces and men adopting certain attributes associated with femininity. If my primary source of identity comes from the fact that I belong to the category “man,” then my identity is very insecure, since “man” tends to entail a strict set of behaviors and expressions: I must be strong, stoic, dominant, wise, warrior-like, brave, and assertive. I must be a leader, I must be able to labor or fight, I must father children. The problem is that if I fall sufficiently short of these attributes while still wishing to be called a “man,” either “man” must be redefined or I must be removed from the category altogether, both of which put my identity and that of my fellow men at risk.

“No one is more arrogant toward women, more aggressive or scornful, than the man who is anxious about his virility,” Beauvoir writes, and we can indeed see this play out quite frequently. Men who abuse their wives and children often do so precisely because of their desperation for their sense of identity, their position within the category of “man,” to feel secure. On the subject of sexual assault, Slavoj Žižek explains that “rapes signal the impotence of the aggressor;” despite the appearance of power exercised in such an act, it demonstrates weakness with regard to the ability to have sex by normal, consensual means. And there are “incels” (involuntary celibates) who stew in anger over their lack of sexual contact with women and then proceed to murder them for no reason except in an attempt to drown out their own insecurities. This is why the self-other dichotomy can be so dangerous; if my identity is too starkly contrasted with a specific other, any anxiety over the security of my identity then becomes the problem of that other. And when this relationship occurs between different groups of people it invariably leads to some form of oppression.

We can return now to the subject of LGBT+ oppression since their othering follows a process similar to that of women by insecure men. With the establishment of Abrahamic morals and cisgender/heterosexual normality as unquestionable, gender and sexual minorities became the other against which the “normal” self could be contrasted. And because heterosexuality and strict adherence to the male-female gender dichotomy were essential aspects of the righteous and Godly life, this meant that anything else had to be seen as perverse, depraved, and evil. It is no surprise then why homosexuality has been so closely associated with Satanism and other forms of heresy, since all instances of defiance against the symbolic order to which one adheres end up lumped together as various appearances of the other. Persecuting homosexuals among other deviants therefore became an easy way for good Christians to establish themselves as such.

Some countries, particularly France, made efforts to legalize same-sex relations early in the 19th century, but the movement for LGBT+ rights did not really begin until the end of that century. In Germany, laws criminalizing homosexuality remained on the books until well after the Second World War, but certain social factions began campaigning for decriminalization and equal rights as early as 1897. With the end of the First World War and the establishment of the Weimar Republic, the attitude towards gender and sexual minorities became fairly tolerant. Gay bars and clubs became common in the country’s urban centers, gay publications were circulated, scientists began arguing for their normalization, and the government even considered expunging the article that made same-sex relations illegal.

If it is any surprise, this trend came to a halt when the Nazis came to power. LGBT+ people were, in fact, one of the first targets of Hitler’s regime. In 1933-36, Nazi stormtroopers burned homosexual literature and research on sexology, pro-LGBT+ organizations were forced to disband, and Himmler as the new head of the state police established a special office tasked with hunting down homosexuals. The Gestapo collected names and addresses of suspected homosexuals and trained local police how to target and root them out. Gay men inside the Nazi Party were also purged, the most prolific of them being Ernst Röhm, who had been the leader of the Sturmabteilung and whose sexual proclivities were quite embarrassing for the other Nazi leaders. In all, around 100,000 people were arrested for homosexual behavior. Some were subjected to torture in order to extract confessions. Some were castrated or experimented on medically. Most who were sentenced spent time in civilian prisons, but several thousand ended up being sent to concentration camps to die right alongside the other targets of the regime.

The Nazis persecuted homosexuals as part of their drive to establish a pure and powerful German race, and homosexuality was understood as a contagious disease that threatened to undermine this project. Nazi propaganda accused them of “poisoning” society, of preying on children and spreading their sexuality to them, and of being tools of the Jewish plot to stunt and ultimately destroy the Aryan people. The SS newspaper Der Schwarze Korps declared that homosexuals were “a state within a state, a secret organization that runs counter to the interests of the people.” This is indeed very similar language to that used against the Jews, who were thought to be the primary “enemy within,” dwelling among Germans but loyal only to one another. Thus homosexuals became, as did the Jews, others against whom the pure-blooded, morally upright, masculine German man had to be contrasted.

What must be examined here is the extent to which the persecution of Jews, homosexuals, and other groups by the Nazis can be ascribed to the projection of insecurities in their notions of German purity and masculinity. Most striking is the absurdity of proclaiming the Aryan race to be the most powerful while also claiming that the Jews, who were supposedly running global politics, were the weak and miserable ones. It was doubtless one of the chief achievements of Nazi propaganda to weave narratives such as this that were completely contradictory but still believable. There was also the argument that the German Army did not lose in the First World War but was “stabbed in the back” by Jews and socialists at home, which has been thoroughly disproven by military historians. And projection can be seen in the Nazi charge against homosexuals that if tolerated they would infect children with their sexuality and eventually cause the German birth rate to decrease, putting the survival of the race at risk, while the Nazis themselves were raising children to serve in a global war that would inevitably lead to the deaths of many German soldiers and civilians and put the race at even greater risk of destruction.

For the Nazis, the other was a useful category to deflect guilt for their own shortcomings and to drown out their own insecurities. The Germans had not lost the war, they had simply been betrayed by the other; the Germans were not weak, they had simply been castrated by the other; the Germans were not degenerate or effeminate, they had simply been infiltrated by the other. Proper Aryans were strong, manly, and indomitable, and if they displayed any other traits it was simply the result of the other’s scheming. We can easily adapt Beauvoir’s words here: no one is more arrogant toward Jews (or socialists, or homosexuals, et cetera), more aggressive or scornful, than the Aryan who is anxious about his strength and power.

A major part of what motivates the projection of insecurities onto targets of persecution is the drive to suppress existential anxieties by indulging in sadistic domination of the other. Erich Fromm explains in Escape from Freedom that such expressions of sadism are actually a display of substantial weakness:

While the masochistic person’s dependence is obvious, our expectation with regard to the sadistic person is just the reverse: he seems so strong and domineering, and the object of his sadism so weak and submissive, that it is difficult to think of the strong one as being dependent on the one over whom he rules. And yet close analysis shows that this is true. The sadist needs the person over whom he rules, he needs him very badly, since his own feeling of strength is rooted in the fact that he is the master over someone.

As Beauvoir says, “one of the benefits that oppression secures for the oppressor is that the humblest among them feels superior.” This is the ultimate purpose of targeting the other with such vigor as the Nazi regime did: to give the Germans the appearance of strength which they did not have on their own. “It is always the inability to stand the aloneness of one’s individual self that leads to the drive to enter into a symbiotic relationship with someone else,” writes Fromm, and the Nazis sought to enter precisely this type of relationship with Jews, socialists, homosexuals, and others in which these persecuted groups became “the objects of sadism upon which the masses [were] fed.”

The same can be said of bigotry in other times and places as well. There can be little doubt that a strong sadistic drive motivated the racist militants who harrassed recently freed black Americans during the Reconstruction era; their feeling of superiority had come under threat with the abolition of slavery, and thus they had to re-assert dominance through extreme displays of violence. In the 20th century this continued, with segregationists still grasping at the remnants of their superior social status in their attempts to uphold the separation of races. And with the increasing prevalence of gender and sexual minorities ever since the start of the gay liberation movement in the 1960s, those who are desperate for a sense of strength, superiority, and righteousness have found new fodder upon which to feed.

None of the arguments used against LGBT+ people today are new. In fact, some of them seem directly borrowed from Nazi propaganda, even when those using them are not necessarily fascists. The idea propped up by many conservatives that LGBT+ acceptance is part of a “cultural Marxist” attack on American society is virtually indistinguishable from the idea pushed by Nazi rhetoric that Jews, socialists, homosexuals, and “degenerate” artists were united in a “cultural Bolshevist” attack on Germany. Some of the specific points are the same as well, including the idea that LGBT+ people seek to prey on children, that they suffer from a disease that needs to be treated instead of tolerated, that their existence is a sign of social decay, et cetera. The term “groomer” has come into common use among conservatives to refer to LGBT+ people and their supporters, implying that their identities and lifestyles are inherently dangerous to children, that they all secretly have pedophilic inclinations, or that they wish to indoctrinate children with “gender ideology,” and the rapidly increasing rate of teens identifying as LGBT+ is cited as evidence of this.

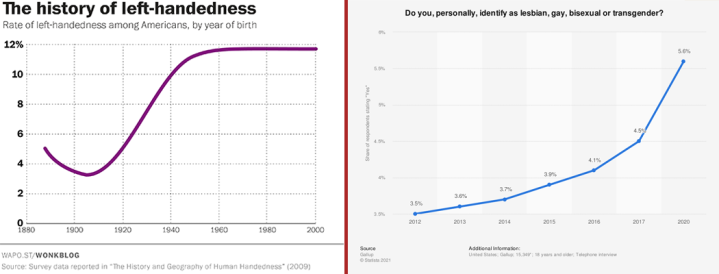

Of course, these accusations are absurd; current science understands that alternative sexualities and gender identities are not a disease, nor are they contagious, and the purpose of normalizing gender and sexual minorities is only to allow people to be comfortable with who they authentically are, not to encourage anyone to be something they are not. When strict regulations on some aspect of individuality are lifted, there is always a surge in divergence from the norm; one does not need to look further than how the rate of left-handedness increased suddenly when teachers stopped trying to “correct” left-handed students in the mid-20th century to understand that this is natural. Teachers did not start “grooming” children to be left-handed, they merely let the students write how they were most comfortable writing. This is precisely what is happening for American children as they are growing up in a world more tolerant of alternative identities and lifestyles, and if there is any pressure for them to adopt one of these, it can not compare to the pressure to adhere to strict traditional prescriptions of behavior and expression that has only recently begun to be lifted.

The absurdity of arguments in favor of oppression, however, is often to the advantage of the oppressor; as mentioned earlier, it was not necessarily the goal of Nazi propaganda to make sense or to be factual in any way. Hannah Arendt explains that “its audience was ready at all times to believe the worst, no matter how absurd, and did not particularly object to being deceived because it held every statement to be a lie anyhow.” She further states that “what convinces masses are not facts, and not even invented facts, but only the consistency of the system of which they are presumably part.” What is consistent here is not reality and its laws, not science, history, nor even morality, but the conflict against the other which is perpetuated by whatever means necessary, no matter how dishonest, manipulative, or ridiculous.

We should indeed work to protect our society’s children from physical and psychological threats, but time and time again it is proven that those threats largely do not come from the left but from the right, not from LGBT+ people or activists but from religious conservatives. Child abuse, incest, and teen pregnancy are correlated with religious conservatism in the United States, and many of the conservative politicians most outspoken against pedophilia and LGBT+ rights have been caught in child pornography, rape, and sex trafficking scandals. “Sexual abuse is the most underreported thing” in religious communities according to prominent evangelist Billy Graham’s grandson, Boz Tchividjian, an attorney who specializes in church-related sexual abuse. He cites one particular instance when a pastor refused to report a child molester “because the man had repented,” enabling him to molest five more children before he was finally caught. Yet those at the pulpit seem to only ever speak of the threat coming from the other.

Further examples of how children are harmed by the right include the continued popularity of corporal punishment in conservative families despite the psychiatric consensus that it only causes harm to children. Conservatives also seem to think that child grooming is not a problem if done the “right way,” as the Tennessee Republican Party is currently sponsoring a bill that would remove the age limit for marriage in the state. And conservatives often demonstrate a shocking lack of understanding and concern for the effects of sexual assault, even against young people; a Republican candidate in Michigan, Robert Regan, stated on a livestream that he has told his daughters “if rape is inevitable, you should just lie back and enjoy it.”

What we can see in the accusations against LGBT+ people of posing a threat to children is the same deflection apparent in other instances of oppression. Even if a member of a religious community is caught doing something just as bad or even worse than what the other is accused of doing, they being part of the in-group are spared the same judgment. As journalist David Atkins puts it, religious conservatives are “offered an endless cycle of atonement & redemption through prayer–reinforcing the social order and allowing them to abuse again, only to be redeemed and ‘forgiven’ again endlessly.” The group can not risk confronting its own insecurities, its own flaws and shortcomings, therefore just as the Nazis projected their insecurities on the Jews, American conservative communities must do the same with their choice opponents.

American conservatives by and large never take kindly to being compared to fascists, and it must be acknowledged that some strains of conservatism are much more benign than others. Yet it can not be denied that the further conservatives lean to the right, the blurrier the line between their ideology and fascism becomes. When American neo-Nazi and Holocaust denier Arthur Jones ran for Congress as a Republican in Illinois, he won 58,000 votes. This was after saying in a campaign speech, among various xenophobic and nationalistic remarks, that he wanted to put gay people “back into their closets.” Only two conclusions can be drawn about those who voted for him: either they were totally ignorant of his ideology (which itself does not reflect well on the Republican electorate), or they preferred a literal Nazi to a liberal Democrat. If the latter was indeed the case for some of the Republican voters in Illinois, it is not at all surprising how so many German conservatives ended up supporting and collaborating with the Nazi regime.

The most common argument used by conservatives to deflect association with fascism is that LGBT+ rights advocates are the real fascists, that gender and sexual minorities are threatening their freedom by forcing their ideology on the country. Here again we see the same process at play outlined in Beauvoir’s analysis of patriarchal oppression and in Fromm’s understanding of sadomasochism. The oppressor comes to mistake their position of superiority as essential to their identity, and hence threats to it are perceived as threats to their very life and freedom. If I as a man depend on dominating women to achieve a sense of manhood, of course my manhood will be threatened if I am forced to see women as equals. If I as a white person depend on being superior to other races in order to feel secure in my identity, of course that identity will be threatened if I am forced to treat members of other races as my equals. And if I as a conservative evangelical Christian depend on feeling morally superior to people who practice other religions or live other lifestyles, of course my identity will be threatened if I am forced to accept those other people as normal, respectable, and no more prone to moral deficiency than myself.

It is just as telling to accuse gender and sexual minorities of being the real oppressors, when on average they are 30% more likely to be impoverished, 120% more likely to be homeless, 350% more likely to commit suicide, and nearly 400% more likely to be the victims of assault than cisgender and heterosexual people, as it is for the Nazis to have accused the Jews of being the real oppressors when they were so frequently victims of anti-Semitic scorn and persecution throughout European history. Of course, some Jews held privileged positions in German society, and this was used as evidence of their stranglehold on power, but the vast majority of them were marginalized and no more wealthy or powerful than the average citizen. Likewise, the academics and public figures pushing for LGBT+ rights are identified by conservatives as evidence that they are taking over society and imposing their will regardless of the powerlessness and alienation of the majority of LGBT+ people.

The problem for conservatives is not that they are actually being oppressed by those who have different identities and lifestyles, nor simply that the existence of conservative values is under threat due to the tolerance of alternatives. The problem is that the reactionary mindset needs an other to which it can react. Beauvoir makes this point with regard to the conflict inherent in traditional gender roles:

In those combats where they think they confront one another, it is really against the self that each one struggles, projecting into the partner that part of the self which is repudiated; instead of living out the ambiguities of their situation, each tries to make the other bear the abjection and tries to reserve the honor for the self.

Because conservative values almost always include a belief in some form of hierarchy–a belief that certain types of people are naturally superior to other types–a good conservative desperately needs an inferior in order to secure their own identity, to “reserve the honor” for themselves. If LGBT+ people fall out of favor as the chosen other, some different group will take their place. This in fact already happened over the past century as racism against blacks became less socially practicable and conservatives gradually shifted their focus to other opponents.

The solution to this problem must start at its roots, at the existential tension between the self and the other. It is a simple matter of fact that I need others against whom I can be contrasted in order to really have a sense that I am an individual. It is also a matter of fact that as an individual I am inclined to identify with groups of people who are similar to me in certain ways. But when the group is prioritized over the individual–when the fact that I am, say, a Baptist becomes more important than the fact that I am an independent human being–things take a turn. I adopt whatever is prescribed to me as a Baptist and lose my sense of individuality, my sense of responsibility for who I am. As long as I adhere to whatever my particular group deems proper forms of behavior and expression, I can claim to be secure in my identity.

This particular way of thinking is most often called “identity politics” and is associated with the left in modern society, and to an extent it can be seen as a legitimate shortcoming of some leftists. But in spite of the individualistic rhetoric they so often use, members of the right are absolutely the worst practitioners of this type of thought. They tend to be much more embedded in group identities such as nationality, ethnicity, religious denomination, et cetera than people on the left, and much more isolated and fierce in defense of the boundaries around their group. And conservative ideologies such as nationalism, militarism, religious fundamentalism, and racism have been proven to bear such immense potential for human destruction that any comparison to left-wing group identities (with the exception of things like Stalinism) is absolutely preposterous. We should not need to recount the atrocities of slavery, the Civil War, the World Wars, the Inquisition, the Crusades, the genocide of indigenous people by colonists, nor the roots of any of these tragedies in the aforementioned ideologies to make this point clear. Yet these are still the ideologies that conservatives cling to and seek to continually rehabilitate each time their danger is shown.

Fromm concludes in his examination of Nazi psychology that no matter how functional a strict, authoritarian system of social order might seem to be, it is only a mask for the underlying existential anxieties, to which it can not effectively respond:

The function of an authoritarian ideology and practice can be compared to the function of neurotic symptoms. Such symptoms result from unbearable psychological conditions and at the same time offer a solution that makes life possible. Yet they are not a solution that leads to happiness or growth of personality. They leave unchanged the conditions that necessitate the neurotic solution… The escape into symbiosis can alleviate the suffering for a time but does not eliminate it.

In other words, even if conservative factions succeed in suppressing LGBT+ people entirely, the need for an other with which they can enter into a symbiotic relationship will persist indefinitely. If such a faction could somehow reach the point when all identifiable others have been effectively done away with, the sudden lack of external tension keeping the group intact would lead to its dissolution, because the lack of a contrasting agent would mean that the group’s identity would no longer have a point of reference. Members of the original faction would then be likely to split into opposing groups once more, perpetuating the battle for dominance ad infinitum.

What Beauvoir ultimately reminds us is that “the fact that we are human beings is infinitely more important than all the peculiarities that distinguish human beings from one another.” Individuals are not a threat to one another in themselves; a woman is not a threat to a man, and a gay or nonbinary person does not detract from a straight or traditionally masculine person by their mere existence. It is only when one becomes associated primarily, for example, with the category of heterosexual people when the existence of an opposing category of homosexuals appears threatening. I as an individual am fundamentally equal to any other individual, no matter our differences in identity, but if I become deeply invested in whatever privileges or benefits come from my identity as a certain type of person, that categorization suddenly becomes more important than my individual humanity when those privileges are called into question. I am then forced to fight for a superior position and to negate the full, authentic humanity of whoever I seek to keep as an inferior.

If, on the other hand, I establish an identity that does not depend on my being superior to others, but rather on my individual ability to grow, to flourish, to be the best I can be in all that I do, there is no need to see the flourishing of others as a threat. The growth of the individuals around me instead becomes a source of inspiration and encouragement, no matter how different they may be, since I can see the essential humanity that underlies their development and relate it to that within myself. The powers I develop then are my own, not those that I only appear to have by grasping at a position of categorical superiority, and I am motivated to acknowledge and contend with whatever my personal anxieties and insecurities might be rather than projecting them onto another person and using them as a receptacle for my own self-loathing.

There is a degree of existential security and satisfaction that simply can not be achieved through oppressive means. A sense of self built upon superiority over the other will always be insecure because of the fear that the other might slip out from under one’s boot and flip the relationship on its head. And the projection of an individual’s failures onto the other never actually addresses those shortcomings; the anxieties they produce live on and only make the individual more and more desperate to keep them covered. Thus the marginalization, the abuse, the sadistic domination, the violent oppression that results can simply have no end. As Fromm puts it in Man for Himself, “even if a person seems to be destructive only of others, he violates the principle of life in himself as well as in others… We find that the destructive person is unhappy even if he has succeeded in attaining the aims of his destructiveness.”

The satisfaction of our deepest existential needs can only be found in mutual liberation, in the casting off of prejudiced and hierarchical ways of thinking, in the celebration of human individuality and all its potential. As long as we refuse to pursue this end, our hopeless grasping at a position of racial, national, moral, or sexual supremacy will continue to culminate time and time again in atrocities of a historic magnitude. We must apply Beauvoir’s words about the relationship between men and women to all authentic yet contrasting identities: straight and gay, cis and trans, black and white, familiar and foreign, introvert and extrovert, thinker and actor, speaker and listener, modest and proud. “They have the same essential need for one another, and they can gain from their liberty the same glory. If they were to taste it, they would no longer be tempted to dispute fallacious privileges, and fraternity between them could come into existence.”

-Jordan

Featured image depicts homosexual prisoners in Sachsenhausen concentration camp. These men were made to wear pink triangles on their uniforms to distinguish them from other prisoners, and today the pink triangle is used by LGBT+ people as a symbol of their struggle for acceptance. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.